Steering wheels

By developing an orbital model for change management that puts FM at the centre of the process, Edward Finch sees a better connection with the bigger picture.

By Edward Finch

Once it was simple to describe facilities management as “any activity that supported the operational activities required to support an organisation”. However, the agenda has moved on. No longer is the FM’s role one of keeping a ‘steady ship’. An increasing proportion of their activities are project driven, innovation led, with increased stakeholder complexity. And they are user-centred, with the requirement to accommodate the views of users in a much more participative environment.

What does published theory and research have to tell us about the management of change? What relevance does it have for the hectic daily demands of the facilities manager? The reality is that, despite the explosion of self-help books and ‘how to’ recipes, very few of them are ‘fit for purpose’ in the context of facilities management.

Firstly, they often fail to acknowledge the significance of facilities and the instrumental role they can play in transforming an organisation. Attempts at business process re-engineering often fail, as organisations flit from one ‘flavour of the day’ to the next. No attempt is made to communicate change through workplace design, rebranding of the reception area or the reshaping of habits within the built environment. Perhaps more invidious and my second point is that most theory relating to change management lacks context. Many address only an isolated aspect of change (eg, culture, workplace design, process design); while others put forward a single approach to change (eg, ‘organisation development’ ; ‘systems thinking’ or ‘strategic planning’). No wonder the facilities management profession is reluctant to spend time making sense of such a convoluted collection of ‘recipes’.

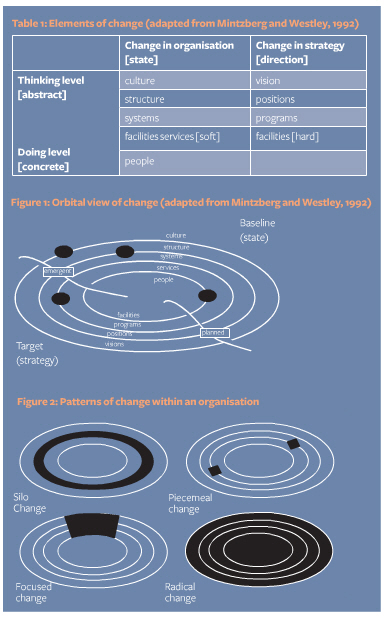

But facilities managers have a key ally in the world of management theory. Henry Minzberg, one of the leading lights of modern management thinking, acknowledges the central role played by facilities and their services in realising change. Writing with Frances Westley, Minzberg attempted to confront the problem wherein ‘by seeking the explain the part, we distort the whole’. In their key publication Cycles of organizational change they describe a ‘system of moving circles’ (like a bulls-eye) to represent the various aspects of change at differing levels of abstraction.

In Mintzberg and Westley’s view of the world, change can take place from the broadest conceptual level (e.g. in the minds of organisational thinkers) to the most concrete and tangible level (this might include a person in a job, a piece of technology or a piece of real estate). But, they argue, such chance also occurs in one of two spheres; 1) the basic state and 2) the thrust or direction of the organisation. Put together, we end up with the total landscape of change which confronts an organisation.

Two spheres

The two spheres of state and direction define the two spheres of activity facing the modern day facilities manager. The ‘state’ is about what you have got. We can reconfigure organisational services, delivery systems and people to satisfy the changing requirements of an organisation. Service level agreements can be modified, maintenance staff can be redeployed and space plans rearranged. Such changes often occur incrementally, over days, months or years, often in a piecemeal manner (what Mintzberg calls the deductive change). While these changes may be largely unplanned, over time they can have a profound effect on an organisation. Contrast this with the second sphere, ‘change in strategy’ which involves planned change and determines the direction of an organisation. It is this second sphere which is increasingly the territory of the facilities manager, demanding a project management approach and longer term planning.

It is these two distinct spheres which exemplify the two worlds of ‘facilities management’ and ‘real estate’. The two were often set apart, with facilities solutions allowed to evolve in response to changing demands. In contrast, real estate involved key strategic commitments with the impacts unfolding over many years, often as part of a master plan. However, things have changed fundamentally. New innovations in workplace design, sustainable transport planning, and energy initiatives among others have transplanted the activities of the facilities manager from evolutionary planning to project planning. The worlds of facilities management and real estate have begun to converge. Real estate has started to adopt the language of ‘user-centred’ behaviour (state), while facilities managers have embraced visionary language (strategy) previously confined to the real estate role.

Orbital model

In Figure 1 we present the ‘orbital model’ of change management. Based on the moving cycles of Mintzberg. Like Mintzberg’s model, it recognises that change can take the form of circumferential change (moving from the outer abstract level to the inner concrete level). However, unlike the spiralling view of Mintzberg, the orbital model proposes that a quantum of energy needs to be expended in order to move up through to outer levels. Without the necessary energy input, the change management initiative falls back to its original state. This energy might be referred to as the ‘transition energy’ (using the parlance of atomic theory). Change can also occur at a single orbital level (what Mintzberg calls circumferential change) so that the impact of facilities changes may be confined to people and workplace, without a more abstract impact on structure or culture within the organisation. This gives rise to isolated pockets of change (see Figure 2), either at a discrete point on the orbital path (isolated change) or within a single ring (silo change). Thus, the introduction of new ways of working may be introduced at the ‘people’ or ‘facilities’ level but without the additional input of energy to bring about an impact on the ‘systems’, ‘structure’ or ‘culture’ level. At the other extreme, an orbiting object (change initiative) may reach ‘escape velocity’ propelling the organisation into a new ‘realm’ of sequences and patterns of change.

So who needs another change management model? The value of Mintzberg’s original model is that it places facilities management ‘centre-stage’, unlike most change management models which make only passing reference to facilities as a vehicle of change. For those seeking to leverage support for facilities management initiatives, the ability to contextualise the change is paramount. Is it an isolated approach, a piecemeal approach or perhaps a revolutionary approach? The orbital model also highlights those areas of change where further investment of energy is required to transform an isolated or piecemeal approach into a more focused or revolutionary approach. The model demonstrates graphically the two realms of real estate management and facilities management. While the former is typically driven by formal change often in the form of a structured acquisition process or perhaps as part of a master plan (the top-down approach), facilities management makes much more use of a bottom-up approach, in the form of informal, emergent change.

For corporate organisations seeking to roll-out change on a global arena, having a holistic view of change is paramount. Such an approach allows innovation to be fully exploited in various geographical regions and at different levels of abstraction within an organisation. It is hoped that the proposed roadmap provides a useful tool that will allow more effective engagement between the concrete world of the facilities management team and the conceptual aspirations of organisational leaders.

Edward Finch is professor in facilities management at the University of Salford.

References

- Finch, E., (2009) Flexibility as a design aspiration: the facilities management perspective, Ambiente Construído, Vol. 9, No 2

- Mintzberg, H. & Westley, F., 1992. Cycles of Organizational Change. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 39-59